This piece was originally commissioned by Scottish writer Cara Ellison to appear as a 500-word blurb in Paste Magazine. It did not end up appearing in Paste Magazine—mostly because the author was an absolute God damn mess as a result of being submerged in the psychedelic fever dream called “Los Angeles” for way too long. Deadlines were missed, calls went unanswered, and absolutely no one cared.

The following words, all twenty-five thousand of them, were written in dark places and at late hours with a sort of manic desperation not previously thought possible. In all likelihood this is probably the worst thing anyone has ever written. We present to you now a coffin filled with spider parts—a rotted ugly mindscape where no good thing grows. Its existence, though awkward, is pure and unedited. Please enjoy.

PART ZERO:

GOIN’ DOWN TO SKELETON TOWN

The Doomsmobile rolled onto Sunset Boulevard at exactly midnight, the two of us strapped inside, my partner and me, feeling like hell and looking it too. For six hours and three hundred seventy miles we had rocketed down that dark empty California highway, guzzling black coffee from mason jars and smoking dozens of cigarettes and popping little pink pills till our nerves were useless. And finally, by God, we had arrived in the city of Los Angeles, scarcely understanding why we had come in the first place. . . .

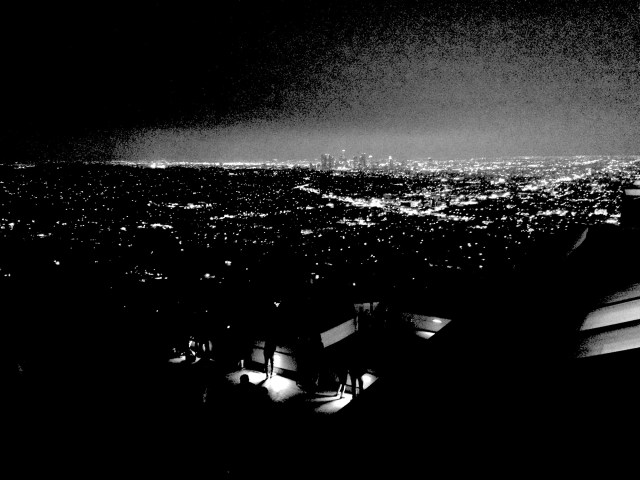

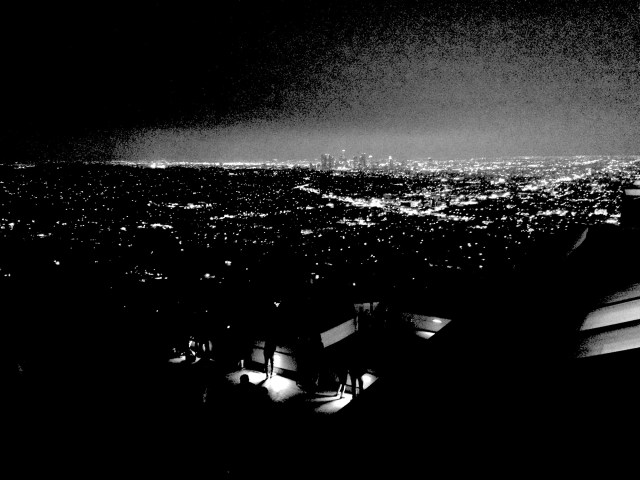

I was slumped over the wheel, mindlessly steering that haunted cartoon car up and down the street as tears of exhaustion collected under my drooping eye sockets. My brain was slushed to hell and I was vibrating past reality big time. I absorbed external stimuli as it came to me—the palm trees, the stupid billboards, the lights in the hills—and then, like a radio transmission from the moon, I endured the few seconds of dead air before the noise and the lights were received at mission control.

Only I knew there was no one at the switchboard . . . just a frightening room full of blown circuitry and sparking wires dangling from the ceiling. Flickering fluorescent lights and static on every monitor. Maybe a distant scream from down the hall followed by an eternity of silence.

The Doomsmobile’s headlights carved through the stillness of Silver Lake as I swerved erratically in the dark, thinking that maybe we would be dead soon enough. There was no doubt about it: we were food for the Reaper. Yes, it really was only a matter of time. . . .

I didn’t say anything about this to my partner. He was silent in the passenger seat, his eyes hidden behind cheap sunglasses and layers of caffeine and speed. The poor bastard was blissfully alone inside himself just then. No sense telling him he wasn’t long for this world.

I turned down a side street and parked next to an overflowing dumpster. I killed the engine and sat there for a moment, fooling around with the FM tuner. “Don’t Stop Believin’” was playing on three separate stations, each of them about thirty seconds apart. There was bug shit all over the windshield.

“I get this town,” I said finally. “I get these people. Holy lord, I like it here. What a strange thing for an animal to build.”

Hearing my voice, Jack was ejected from some nightmare inside his head. He opened his eyes and stared blankly at the one outside of it. “You talking about Los Angeles?”

“Yeah. Hell, I just like it here. You know? You can be the biggest fucking wasteoid on the planet and no one cares. That’s beautiful.”

“I suppose it’s a place people like.” He leaned the chair forward and looked out the window at the dumpster. It was inches from his face. “Seems about right, parking here.”

“Yeah. I like it when they make the metaphors easy like that.”

“Saves us all some time.” He yawned. “Maybe we should crawl inside the thing and go to sleep.”

“Listen,” I said. “I called my friend Amy when we passed through Santa Clarita. You were still asleep. She wants to go to a bar with me. I told her I would, and now I’m going to do it. I’ve got to. I’m sorry. I’ve really got to see that girl.”

“Now?”

“Yeah. I’ll have a few beers and that’s it. And then together you and I can plunge into this God damn thing like brothers and see what happens.”

“Hm. OK.”

The kid wasn’t getting it. He was still staring at the dumpster. I switched to my serious voice to amplify my desperation: “Jack, baby—I need this. For God’s sake, the rest of the week is going to be miserable as hell. Jesus, the rest of my life. . . .”

“Then go see your lady friend, man. I’ll find something to do. Plenty to get into in this city, at this hour. I’m sure of it.”

Jack reached into a paper bag at his feet. It was filled with a week’s worth of rations we had brought with us from Oakland: nuts, carrots, cabbage, tangerines, wasabi peas, a loaf of sourdough. He took out a little Gala apple and tossed it to me. I caught it with the numb fingertips of my left hand. The amphetamines had destroyed my circulation. I couldn’t feel the apple, but I trusted it was there.

I took a bite and started the engine. It idled smoothly—a fine sound. Eyeing the illuminated panel I saw that we still had half a tank left from our fill-up in Lost Hills. Probably wouldn’t last long, I thought, not in this town . . . but then neither would we. And anyway we both knew it was all for nothing—all that gas, all that time, all that poison taken in through our gills. Our health, mental and otherwise, was circling the drain. We’d been there less than five minutes and I already knew the assignment was a total bust.

In the rearview mirror I watched a silver Prius stop near a row of cars. A man was driving. A woman got out of the passenger seat. She waved to the man and took out a set of keys from her purse. She used them to unlock another silver Prius that was parked nearby. The first silver Prius drove off. It was one of the most ‘California’ things I’d ever seen. I laughed.

“Well!” I said. My chest ached just then. I supposed I was bleeding internally. No more words came to me.

Jack leaned the seat back and rubbed his forehead with his hand. “Take us there, wherever there is,” he said. “And then I’ll vanish for a little while so you can see your friend.”

• • •

PART ONE:

AMY AT THE AKBAR LOUNGE

I drove to Amy’s house, which was less than a mile away. Her street was lined with sick and crooked palm trees fifteen feet high. The street lamps were dim. Every house was dark. I parked the car by a gutter and got out.

Jack slid across the gap between the two front seats and planted himself behind the steering wheel. He had taken his off his sunglasses and now I could see that his eyes were spiderwebbed with pink veins. I hovered over him in the doorway as he placed a cigarette between his lips.

“Do something about yourself,” he said. “You smell like a bag of garbage.” There was a little glow coming out of his brass-plated Zippo. He held his cigarette up to the flame. The fire revealed the creases beneath his eyes. He snapped the lighter shut. He’d been twenty-three years old for less than three days.

“I am a bag of garbage,” I said. “Didn’t I tell you? Lord, if only you knew the extent of it, you’d scream. . . .”

“Yeah, well. Maybe she’ll be into it.” He reached for the door and I stepped back. He slammed it shut and rolled down the window to let the smoke escape. “Some of them are, you know.” The Doomsmobile glided away, taillights glowing red like the eyes of some sad and ancient animal. It turned a corner and was gone from sight.

Amy was standing on the sidewalk when I spun around. Her skin was glowing white. She was wearing red lipstick and a faux leather jacket and a black dress that looked like a huge T-shirt. I felt something in my body twist and turn. It was a good feeling. God knows I hadn’t had one of those in a long time. I wanted to walk over and kiss her, thinking it would be kind of neat, and not altogether terrible.

But I didn’t. I just stood there in the dark not saying anything, partly because I was a screaming black hole disguised as a cartoon character, and I figured kissing something like that must feel absolutely awful. The other part of me was too tired to move.

“Hi Starbaby,” said Amy. “Did you just get here?”

“Hi Amy. Yeah.”

“How was it? The getting here?”

“Oh, it happened.”

“Well, here you are. And now where should we go? There’s a place around the corner called Akbar. It’s mostly filled with middle-aged gay guys. Also, it’s shitty and dark. That’s what you said on the phone, yeah? That you wanted to go someplace ‘shitty and dark’?”

“Aw, hell,” I said, “I love shitty and dark. I only ever want to be around shadows anyway. Especially right now. God, I certainly don’t want to have to see any faces. . . .”

I stumbled over to her. I stood on the street, still in the shadows. Any closer and she would have seen the grease and sweat in my hair and the cigarette ash on my denim jacket. She would have seen the complete lack of anything going on behind my eyes—just a bunch of sawdust and shredded newspaper spinning in the void. She would have smelled me.

“Jesus, lady,” I said. “How many times you gotta pray to Satan to look like that?”

I was delirious; I was mad. I had no idea what I was saying or why I was saying it in the first place. Pray to Satan? What in God’s name did that even mean? Amy was a knockout, though. I knew that much. Maybe Satan really did have something to do with it.

“Every night for a decade, Starbaby,” she said. “Let’s go.”

Amy lead the way. Together we snaked through the haunted alleyways off Sunset Boulevard. Left here and right there, swirling colors, patches of complete darkness, and plenty of cruel, sad places in between . . . finally cutting across the Taco Bell parking lot, past little clusters of chewed and mangled nobodies—those poor ugly souls who have nothing to do, no place to be, and none of the powers of youth to convince the world otherwise. They leered at us with dilated pupils. I wondered what lived inside their heads.

In minutes we arrived at a dimly-lit building that I hoped was a portal to the afterlife. Amy dove into the thing and I flopped around behind her. Once inside it took a moment for my eyes to adjust. This was a dark, dark place. And looking around I saw that there was no sign of judgment or eternal rest. There wasn’t a single pit of flames. It was just another bar, and I was just another jerk.

“You got I.D.?” said an old man in a vest and a conductor’s cap. He was sitting at the corner of the bar eating ice out of a highball glass.

Amy took out her wallet. The man waved her away with his hand. “Forget it, sweetheart,” he said smiling, probably because Amy was Amy. “I was talkin to the kid behind you.”

I placed my index finger to my chest and mouthed “Me?”

“Yeah, Mr. Cool Guy, I’m talkin bout you.” He rolled his eyes and sucked down an ice chip.

I handed him my driver’s license. I’d gotten it a few months before at a DMV in Oakland. In the picture I looked tired. I hadn’t slept the night before. My hair was greasy and my skin was bad. There was no denying it was me.

He pointed a flashlight at it. He moved the light across the surface of the card. It shone through a little dotted bear stamped between the plastic on the right side. It was an outline of the California bear, the same one from the flag—a security feature I had never noticed before.

“Yeah all right,” he said, handing it back.

Amy was already at the bar. She was ordering a gin and tonic when I walked over. I thought about how much I disliked gin and tonics, how sick they had made me whenever I drank them.

“I want to get your drink,” I said to Amy. I didn’t mean for it to sound cavalier. I hoped she hadn’t interpreted it that way.

“Are you sure? Didn’t you tell me recently that you were broke?”

I called her “baby.” I didn’t mean for that to sound cavalier either. I call everyone “baby”—including my own father. But maybe she didn’t know that. Probably she didn’t.

“Baby—” I said, and I really let that pause sink in. “I’m broke as hell. I’ve been broke my entire God damn life. Probably always will be broke, too.”

There was a sort of grinding in my brain. Language and time and memory slipped away from me, fell down a hole somewhere. The lights dimmed and the machinery halted. All I could do was breathe. A dozen or so lifetimes passed. Actually, less than a second had elapsed in the Here and Now—in the world that Amy and everyone else in the bar presumably still inhabited.

“But anyway,” I went on, hoping Amy hadn’t noticed my temporary insanity. “I’d like to get your drink. My expenses are covered, so don’t worry about it. Hell, I won’t be.”

“What do you mean your ‘expenses’?” she said. It was a valid question. Even I hardly understood what I had meant by that. I also didn’t have much of an answer. I tried anyway:

“The Scottish writer who was living on my couch in Oakland—the one who sent me here for the assignment. Well, she gave me some fun money. She said, ‘Go ahead and have a few drinks, if that’s what you feel like doing.’”

I was losing it. Too much spook smoke from the ghost chimney. Too many pills on the ride down. Fun money? Expenses? Cara Ellison hadn’t said any of that. I was fairly sure she hadn’t. But then I couldn’t hear myself talking. Not clearly, anyway. I wasn’t in the Akbar lounge on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, California—I was hundreds of thousands of miles away, drifting soundlessly through a starless vacuum and feeling only the faintest traces of my earthly body. Little pinpricks of pain all over—like ants on a beast which has fallen for good but still beats on anyway, though not for long. . . .

“That’s nice of her,” she said emptily. “Why is she doing that?”

“Well, see, I did her a series of dark favors.”

“Oh?”

“Yeah. Weird stuff. I can’t talk about it right now.” I looked around the room. “I don’t know who’s listening. We could have been followed.”

I turned to the bartender. I slapped my hands down on the bar. “What’s the cheapest crap you have? Is anything here two dollars?”

He made a face as though he didn’t like my shape. I didn’t blame him. I didn’t like my shape either. “Anchor Steam on draft is three.” he said, and it seemed to pain him to have to talk to me.

“God, yeah, I guess I’ll have one of those,” I said. Anchor Steam was made in San Francisco, that rotten place, and I wanted nothing to do it. I had an assignment; I was on the job. I had come to Los Angeles to work, and to get away from San Francisco. I didn’t want to drink its beer. But I had no choice. As I said to Amy and the bartender and anyone else who was listening: “I mean, Jesus, if it’s three dollars, what can you do. . . .”

“Here you are,” said the bartender. He placed a foaming glass under my nose. It was filled with a molasses-colored liquid. He held up both hands and displayed nine fingers. “With the gin and tonic that’ll be nine bucks.”

I handed him my debit card and tried to remember how much money I had in my account. I was sure it was more than nine dollars, but not much more. Those terrible numbers—that whisper of a promise! None of them were real, and yet they governed my fate.

I really did ponder my fate, right then and there: Two drinks now, I thought, but surely there would be more later. And bars were for fools and suckers, and I was a fool and a sucker just then. How in God’s name was I going to afford to do anything after this? How would I complete the assignment? What was the assignment? When would I bathe next? Where would I sleep? How would I afford to eat? And on and on.

Older men with mustaches and haircuts they had definitely paid for were all around us, laughing and kissing and talking in low voices. The bastards had taken all the good seats too. Amy and I were left with an obnoxiously tall table across from the bar. There was a bench on one side and two stools on the other. Amy sat on the bench, and I sat next to her to avoid having to use the stools, which were at least four feet off the ground.

“What kind of asshole wants to use a stool like this?” I said. “Why do they do this to us?”

“I don’t know!” said Amy. “But they are dumb. The stools, that is. Hella dumb.”

I had lived in California for over a year, and “hella” was still a flaming plastic flamingo in an otherwise immaculate yard. It was a peculiar thing to behold whenever it passed through my brain. Amy had taught me “hella” on the first day we met—back in The Mission in San Francisco. That was a year ago. We went to a corner store and I bought her a beer, a Racer 5 IPA, saying, “Do you like these?” And Amy had said, “Those are hella good.” I must have made a face when she said that, because she quickly explained that she had used “hella” ironically, since “only fifteen-year-olds say that.”

I had heard plenty of people much older than fifteen unironically use “hella” since then. I wondered what that meant.

Back in the present, in Los Angeles, an Amy one year older than the Amy I once knew moved her body closer to mine. She whispered, “You hate this place, huh? It’s OK if you do, Starbaby. Maybe I hate it too.”

“I don’t hate it more than any other bar, I reckon, or any other place on planet Earth for that matter. I’m shredded and beat-down and rotten from the inside out. I just feel strange is all. Who cares about the window dressing? That’s all it is. I don’t even know what day of the week it is most of the time. I don’t know what day it is now.”

“It is strange, sitting here,” said Amy. “Everyone can see us. Our backs are against the wall but I still feel exposed.”

I wanted to say to her: Sister, my back is always against the wall, if you know what I mean. And I always feel exposed, if you know what I mean.

But instead I said this: “My favorite seat in a bar is the one all the way in the back, in the corner. Where I can watch all those cockroaches squirm in the dark.”

“That’s a good seat, Starbaby. I like that seat too.”

“It sure is, yeah. I’m glad that seat exists. Maybe that seat is the only reason I ever go to bars in the first place.”

Amy spun the ice in her glass with a little red straw. A few seconds passed. They were silent seconds. They were not awkward seconds. I liked sitting there with Amy. I could have sat there like that for a long while and been perfectly content with the circumstances. But then finally she did say something, probably because it was the question on everyone’s mind whenever I am around them: “Wait, so, what are you doing here again?”

“I really don’t know,” I said. “Bearing witness, I guess. Creating waste. Watching the sand fall.”

“But what about this Scottish writer you mentioned?”

“Oh, the Scottish writer is a woman named Cara Ellison. She’s, uh—she’s from Scotland. And she wrote things that became popular on the internet. Eventually her writing became so popular that she realized she could do it anywhere, and people would pay her for it. So she came to California for a while to write about my friend. Some stuff happened. Man, I don’t know. You know how that goes—when stuff happens. Anyway, she promised me a hundred bucks and a little bit of fame if I came down to Los Angeles and wrote a piece about some expo that’s happening at the Convention Center.”

“What kind of expo?”

“Something about video games. Billion-dollar companies showing us the future—or anyway the future according to some cheese-eating white dudes who wear argyle socks.”

“Well,” she said, “I feel like the whole world is over but we’re all still here anyway. So I don’t care what the future looks like.”

“I don’t care what it looks like either. I reckon I’ll find out tomorrow. Whatever it is, I have a feeling it’s pathetic and sad. And everyone is going to have to suffer through it whether they want to or not.”

• • •

For the next half hour I told Amy how I had wrapped myself in a blanket and collapsed in the back seat while Jack took us south to Los Angeles in that old police car of ours . . . how he could be a gorgeous creature when he abandoned inertia and got to moving fast . . . how we had stopped at a terrifying gas station thirty miles outside the thimble-sized census-designated strip of nothing called Lost Hills, where the reptiles who run everything had managed to fill a thousand square feet with camouflage cowboy hats, hot-pink beer koozies, lighters shaped like handguns, and all that other flashing, shrieking, useless plastic garbage they keep next to the cheese- and jalapeño-flavored sawdust.

“There was this cologne dispenser in the restroom. You wouldn’t believed it. Put a quarter in, turn the knob to your desired scent, all of them bad, hit the metal pump and this poisonous chemical labeled ‘sandalwood’ comes shooting out of this godless machine and onto your hands. A foot away, I kid you not, was a condom dispenser. So the idea is to get all greased up and then buy a condom. That’s a hell of a math equation right there.”

We kept drinking. There was no sign of stopping. Like a drunken moron, I kept telling Amy, “It’s on the company card! It’s all taken care of!”

But there was no company card. The card was mine. The company was me. The company was fucked!

In my brain, which was sputtering and backfiring like hell, I attempted to do some elementary arithmetic in the name of self-preservation. At the rate we were pounding drinks I would be completely broke within the hour. Already I had burned through my gas money and the pittance I had allotted for food and coffee.

Oh, God! My mind raced. It considered the consequences of my recklessness. Amy might have sipped at her drink and imagined wonderful things for herself, but I all I could see was self-annihilation. Yes, and after my funds had run dry, I would be stranded in Los Angeles forever. The story wouldn’t get written and no one would ever kiss me again. My car would explode, or be taken into the sea. My clothes would fall off my body, and alone I would roam the beaches at night, pale moonlight on pale flesh, feeding on garbage and whatever alien vegetation washed ashore. . . .

I’ll have to give her some bogus excuse, I thought, to get us out of the bar. Something about a nightly drink limit . . . Too much of the sauce and I’m useless in the morning . . . My people are counting on me; it is important that I am sharpand aware; there is work to be done; my work is important. And so on.

All jokes, of course—and screamingly hideous ones at that. In reality I was a futureless degenerate sinking in the swamp of my own terrible brain, a hack writer with no credibility. I had come to Los Angeles to write a story, but really I had come there out of boredom and loneliness. And in the span of an hour those two things had finally bankrupted me.

I was floating on a moonbeam, I thought, weightless and cold. I was alive because they hadn’t killed me yet. It would all come crashing down soon enough.

• • •

Amy’s eyes got cloudy. She must have been greatly affected by her gin and tonics. I felt almost nothing. “Smoke with me, Starbaby,” she said. “And don’t judge me.”

Amy took my arm and lead me outside. She sat me down on a low wall near the entrance and stood in front of my legs looking hotter than the flames of Hell. We had a couple smokes and talked about nothing of consequence. It was great.

I was sitting there thinking that I would be happy if nothing ever happened to me again when a man in a cheap leather jacket and a red baseball cap perched himself beside me. He crossed his legs and watched us with amusement.

“You two are cute as fuck,” he said after a few seconds.

“Oh yeah?” I said. And then I looked down at my own shoelaces, suddenly interesting, thinking that as long as I didn’t make eye contact with him, maybe he would go away.

“Yeah. I noticed y’all in the bar earlier. My friend did too. But he’s in the bathroom, probably jerking off. Hah! I told him to join us when he gets out. He loves cuties—maybe even more than me.”

“Who doesn’t love cuties?” said Amy. She flicked the ash from her cigarette.

“Cuties are pretty cool,” I said.

“What’s your sign?” he said to Amy. I rolled my eyes real hard. At least now I knew for sure it was OK to abandon whatever vaporous fumes of optimism were left inside me.

“Leo,” said Amy.

He snapped his fingers and looked pleased with himself. “Knew it. Fixed sign. I could feel it when I came over here. You vain little bitch. I love it.”

“Yeah,” said Amy, still puffing on a cigarette. She stared vacantly at the rows of stoplights that went on for miles down Sunset Boulevard, cycling through their colors for absolutely no one.

The man in the cheap leather jacket touched my shoulder with his hand. I looked at it. I had to admit to myself that it was a beautiful hand. His fingernails were flawless. This son of a bitch had recently had a manicure. “And what about you? You’re definitely a fixed sign too. There’s a lot of strange energy coming out of you, Mr. Stubborn.”

“Uhhhhh,” I said, wondering why I was Mr. [Something] to everyone that night. “I’m an Aquarian.”

“Uff!” He fluttered his fingers wildly. “The Water Bearer! Shoulda known.”

“Yeah, I like water. I’d bear some, I guess, if it came down to it.”

A man in Egyptian-looking clothing and shoulder-length hair exited the bar. He looked side to side, smiled artificially, and approached us with the unnerving gravity of someone who has zero self-awareness. I groaned internally. I knew who he was without having to be told. It was the man who loved cuties. He said his name but I didn’t hear it—either because the sound didn’t reach my brain or I immediately didn’t care.

“I see you’ve made friends with the cuties,” he said. “We thought you two were so cute. He’s like my brother, this guy. Did he already read you? He’s good at it. I’m OK, but not as good as him. I find the cuties, and he reads them.”

The Egyptian motherfucker pulled Amy aside. “I see something in you,” he said. “So many colors!” I heard that much. They walked down the sidewalk a little. I watched them in my peripheral vision, thinking that at any second I would have to get wild. I would have to run full-speed with my arms locked like horns to send that bastard to the ground.

“So what’s your deal?” said the guy in the cheap leather jacket. “I mean, what are you doing?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know what your own deal is? Or what you’re doing?”

“I sure don’t.”

“Hm.” He licked his lips. They were coated with some sort of shiny balm. He tilted his head down and eyed me darkly. “Do you wanna see a picture of my cock?”

“Are you asking me if I want to see your penis?”

“Yeah.”

“All right.”

He took his phone out of his pocket and swiped through dozens of thumbnails. Inside the thumbnails I could see little fleshy penises. Oh God, I thought. Oh lord.

I looked at his socks. They were black and glittery. His dress shoes were iridescent. I thought that was neat. I decided in my own mind that I didn’t really want to see a picture of his penis. I could just look at his shoes until it was time to leave.

“Pretty good, huh? The shoe and sock combo? Not an accident. Just eff-why-eye.”

“It’s a good combination, no doubt about it.”

“You know what they say about shoe size, right?”

“I’ve heard my share of rumors.” I shrugged. “But you know how rumors go.”

He rolled his eyes playfully. He batted his eyelashes, which were glittery. “Oh, please. Don’t be coy, Mr. Aquarian. Like you don’t know. Anyway, would you like to see a picture of my cock?”

“Man, I guess.”

He smiled mischievously and held his phone up to my face. It was at maximum brightness. On the screen was a picture of an erect penis in a well-lit room. Behind it, on the other side of the room, was an open laptop with the default Windows XP wallpaper. It made me sad to see that—to see the laptop with the default Windows XP wallpaper, which was a rolling green hill under a blue sky with little cotton-puff clouds. Why hadn’t he bothered to change it?

“What about this one?” he said. He swiped his thumb on the screen. “You can see my balls better in this one.”

“Those are some good-ass balls you’ve got there.” I was sincere. Sure enough, he really did possess a fine pair of testicles.

“You seen a lot of balls?”

“I’ve seen my fair share of balls.”

“And how exactly have you seen so many balls?”

“I used to go to a Korean bathhouse in my hometown. There were balls everywhere. You wouldn’t believe it. Hell, if I sat down and thought about it, I’ve probably seen thousands of balls.”

His eyes flashed when I said “thousands of balls.”

“Balls, to me, are like feet—” I went on. “They’re either gross or they’re OK. Baby, I’m telling you, you’ve got some balls on you.”

I decided then, on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, California in the year 2014, that I was definitely never going to be an old man. And that time didn’t affect me in any meaningful way. And I would never say “I love you” again. And I would die alone in some faraway place where no humans or animals would ever want to go. My skeleton would roast under the sun or be buried under snowfall, never to be seen again.

Ol’ Sparkle Socks was still showing me pictures of his hook-shaped mushroom-cap penis and his perfectly decent testicles, but all I could do was envision the Los Angeles Convention Center and how I would have to be there in less than twelve hours. I didn’t care about being there. I didn’t want anything to do with it.

“Let me show you a more recent picture,” he said, somehow blind to my expression of absolute indifference. Based on the thumbnails alone, I guessed there were hundreds of pictures of his penis on his phone. I began planning my escape.

Briefly I considered calling Jack to say the whole thing was off and that we should get out of town as soon as possible. But I was broke, and I figured I didn’t have long to live—and hell, I thought, why not do something with the time I had left? Plus that hundred bucks from Cara Ellison would go a long way for me once I got back to Oakland. I’d be able to buy so many loaves of bread.

My head ached and my fingertips burned. Amy was still talking to the other twerp and I could tell by the look on her face that she wanted to die too. Do I do something here? I wondered. To stop this? I kept on wondering. I kept listening too.

“Amy, Amy!” the cutie-finder was saying. “You gorgeous animal! I see so many colors!”

• • •

We managed to ditch the creeps after I told them I had to get up early the next day to meet with my probation officer. Amy and I linked arms and walked in the wrong direction to throw off our scent. We wandered beneath the long skinny shadows of palm trees. The moon looked huge and insane. I had already phoned Jack for evac in the Doomsmobile.

“Starbaby, Starboy,” said Amy. “We’re in agreement that everything they said was total bullshit, right?”

“Those boys were feeding us trash, yes.” But then, I thought, show me someone who ain’t.

“Yeah, I just sort of nodded along because it seemed easier than laughing in their faces.”

“The guy I was talking to asked for my number.”

“What? Really? Did you give it to him?”

“I did. I have no idea why. I told him my name was Star Sailor. Just ‘Star Sailor.’”

“He’s definitely going to try to call you.”

“Yeah.”

“Where are you staying tonight?”

“In my car somewhere.”

We were standing at her front gate now. I was thinking that Amy’s half birthday was my birthday, and that my half birthday was her birthday. What did that mean to the universe? What would the guy with the sparkly socks say about that?

“I would invite you in, but my roommates don’t like me.”

“Aw, hell. Don’t worry about it. I’ve got to sleep, anyway, or at least try to. . . .”

“Well, good-night Starbaby.” She flashed a peace sign and disappeared through the gate.

I stood alone on the sidewalk. The temperature outside was the same temperature inside my body. At least it felt that way. I ran my fingers through my greasy accidental pompadour and felt stupid for being in Los Angeles, or anywhere.

The sound of an eight-cylinder engine ripped me out of whatever spiraling nightmare I had crawled into. I saw the headlights and the white roof and the spotlights on either side and knew it was time to crawl into another one. Jack pulled up beside me. He rolled down the window and a plume of smoke escaped and became nothing in the outside air.

“I found a place where we can sleep.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Silver Lake. The Silver Lake. The one this whole trash heap is named for. It’s just a reservoir. Ugly fucking thing. It’s not far. I found it by accident.”

I walked around the car and got inside. Looking over at Jack I saw that the blackness around his eyes had gotten worse and his skin on his face was shiny and bad. We were going to have to lay low. If any taxpayers saw us, we would most certainly be incarcerated.

“You look horrible,” I said.

“I’ll bet,” said Jack. “Shit, I don’t even know what I’ve been doing for the last two hours. Just kinda driving around. Looking at stuff. God, looking at nothing. Hearing things. . . .”

“Let’s go sleep by that Silver Lake and hope no one calls the cops.”

Jack hit the accelerator. The huge engine roared. We were flying down Sunset Boulevard now like two corpses chained inside the cockpit of a rocket ship headed straight to the center of the sun.

“There’s colors on the street,” said Jack, looking haunted. “Red, white, and blue. People shufflin’ their feet. People sleepin’ in their shoes. But there’s a warnin’ sign on the road ahead. There’s a lot of people sayin’ we’d be better off dead. Don’t feel like Satan, but I am to them. So I try to forget it, any way I can.”

“Yeah,” I said.

“I see a woman in the night with a baby in her hand. Under an old street light, near a garbage can. Now she puts the kid away, and she’s gone to get a hit. She hates her life, and what she’s done to it. There’s one more kid that will never go to school. Never get to fall in love . . . never get to be cool.”

“You can say that again,” I said.

“I’ve been listening to this song for hours and I still have no idea what the fuck Neil Young is trying to say.”

“I have no idea what anyone is trying to say.”

“I know you like this one,” he said, and he put on “Celluloid Heroes.” We sang along, my partner and me, just barely, with voices strained and ragged—voices connected to brains cursed with one absolute certainty: that no matter what happened, it wasn’t going to end well.

• • •

PART TWO:

AND THE ELECTRIC SEA GAVE UP THE NEON DEAD WHICH WERE IN IT

I awoke in the trunk of my own car. It was completely dark but I knew where I was when I couldn’t extend my legs. The walls were made of millimeter-thick carpeting. I felt them with my hands and feet. My body was sticky and warm. The whole place smelled like pneumonia. And anyway this wasn’t the first time. The sensation wasn’t alien to me.

Sitting up I bumped my head. With no other choice I curled into a ball and waited for a sign that I wasn’t dead. Outside several cars drove by, making the Doomsmobile rock on its cushy police suspension. I heard birds shrieking and people talking in that upbeat and chipper way that I’ll never understand.

“Jack?” I said to the suffocating darkness. “Are you up there?”

The suffocating darkness groaned. It yawned. It spoke through six inches of fabric and steel: “God. Yeah. I’m here.”

“How was the back seat?” I said.

“About as good as you’d expect,” said Jack. “How was the trunk?”

“Oh, it was all right. Terrifying place to dream, though.”

“A-yup.”

“Did I make any noises? Did I scream in my sleep?”

“Nah. Actually, I figured you’d died.”

“If I’m dead then you’re dead too. And we’re both in the place where dead people go.”

“Then the dead go to Los Angeles.” He yawned again.

In the dark I groped for the plastic eject handle. It was neon green. It glowed faintly. I yanked on it hard. The truck door attempted to fling itself toward the sky. I grabbed it with my other hand and pulled it back down, creating a sort of peephole through which to peer out at the bright world beyond. I imagined exiting the trunk of a decommissioned police car would be a sure-fire way to get an authority figure involved. And see, I had to be sure there were no squares around.

It is wise to assume that almost everyone you see is a square, and if there’s one thing to know about squares it’s that they need to feel safe and comfortable at all times. To them, a disheveled man with no place to sleep registers in their brains the same way as, say, a cockroach infestation does. So they call the exterminator. When you’re dealing with human-sized cockroaches, that means the police.

Two cyclists, both squares, rode past in the bike lane and were gone. I scanned the street for other signs of life and, finding none, let the lid fly the hell open. I sprang up as if I had been trapped in a coffin and hopped out. My feet hit the pavement and I felt as close to being alive as I ever feel.

The world outside my trunk-womb was the color of paper. Every surface was sun-blasted and overexposed. When I had last seen it, it had been dark and dreamy. I had forgotten there would be a different version of everything when I woke up in the morning.

Jack was leaning against a nearby tree smoking a cigarette and tying his shoes. “I heard some people talking this morning,” he said, not looking up, “mostly people walking their dogs, but no one tapped on the window or anything.”

“I didn’t hear a damn thing. It was as if the car had eaten me, along with all my senses and memories. God, it was fantastic.”

“Did you see this fucking thing?” Jack laughed and pointed across the street to the Silver Lake, to the ugly reservoir surrounded by twelve foot fences wreathed in barbed wire.

“Hell of a thing,” I said.

“Hell of a thing,” Jack said.

I coughed. Everything was strange and dumb just then. The future was uncertain.

Miles away, I knew, in downtown Los Angeles, games journalists from all over the world were leaving their hotel rooms, which had been paid for by media conglomerates, so they could fill their stomachs with food, which had also been paid for by media conglomerates.

And there we were, my partner and me, leaning against a beat-up old police car on a residential street bordering a scum-filled concrete hole, brushing our teeth with lukewarm water from a Thermos and swilling down whatever day-old coffee was left in the mason jars while joggers and mothers pushing strollers gazed upon us with confusion and disgust.

• • •

We found a coffee shop a few blocks away and took turns washing our hair in the bathroom sink. I flirted with the barista for a few minutes. I got a bagel and a huge cup of a coffee and ate it on the hood of the car while Jack bought a pack of smokes from a nearby corner store. Once we were fed and washed and properly stimulated, we got on the highway and sat in traffic for forty-five minutes, headed downtown.

By noon we were parked outside a cafe on Hope Street, a few blocks from the Los Angeles Convention Center. Jack stood guard outside the car puffing away while I changed my clothes under a blanket in the back seat. I put on my maroon corduroys and a black T-shirt with a gold tesseract in the center—and my black denim jacket affixed with a little cat pin. Because of all the grease and wax and oil trapped in my unwashed hair, I was able to use my fingers to form it into a sort of oily black soft-serve ice cream swirl. Wrapped around my head were a pair of big white jerkoff sunglasses I use to repel all that is good and wholesome.

“It is a fine day to repel all that is good and wholesome,” I said to Jack, knowing full well neither would be present. I thrust my legs into my pants. “Let’s get out there and shake those bastards up.”

Jack went around the side of the car and popped the trunk. He took out a little Tibetan incense box that I had emptied and filled with drugs back in Oakland.

“What’s the flavor of the day?” he said. I saw him inspecting the goods in the rearview mirror.

“I reckon we should stick with the amphetamines for now. Get our God damn blood pumping, you know?”

I slipped my feet into my shoes, which were resting on the sidewalk, and stood up. Suddenly I was out of the car and in Los Angeles again. Now I was part of the thing. Now there were rules I had to pretend to obey.

“Here,” said Jack. He handed me half a pill. It was pink and chalky. Jack was holding the other half in the center of his palm. We each stared at them, wondering where they would take us, and then gulped them down.

The stuff hit my brain instantly. It tingled and went supernova. I saw vapor trails and ghostly rainbows emerge from every solid object around me—from skyscrapers and postboxes and dogs on leashes; from the Doomsmobile; from Jack’s face. And then time compressed into a single gorgeous moment. It stayed like that for less than half a second before expanding into the same endless corridor of bullshit it always was.

“Whoa,” I said. I shook my head. “They’ve finally done it, haven’t they? They’ve finally made something that works.”

Jack was far away. His eyes were huge pale zeros.

“Ready to mix with the animals?” I said.

Jack was returning to his definitions. He was coming back from outer space. He opened his mouth: “Lord, no, but let’s do it anyway.”

I locked the Doomsmobile and put four dollars in quarters in the meter. That gave us roughly three hours to get the story and get out. Mostly I just wanted to get out.

“How do we find E3?” said Jack.

“We just follow the noise,” I said.

“What noise is that?”

“Whichever one sounds the worst.”

• • •

We were insane by the time we arrived in whichever circle of Hell contains the Los Angeles Convention Center. I guessed it was the Third Circle, that big underground garbage dump where sinners worm around in the icy muck.

We wormed around too, wormed in the muck, my partner and me, no better than the rest of them. Some of our senses were accelerated and others greatly dulled. My eyes spiraled behind tinted lenses. Exhaustion weighed heavily on every miserable bone in my body, in every screaming cell that gave me my shape. I looked over at Jack, who looked spooked as hell.

And who could blame him? All around us was the worst kind of fakery: an island of concrete infected with Satanic architecture and palm trees flown in from God-knows-where; terrible music shrieking into the terrible sky; trailers and buses wallpapered in advertisements for culture-destroying anti-entertainment; an enormous robot sculpture sprouting up from the dead earth below while an amorphous mass of feel-nothings squirmed and scuttled in its foul shadow. . . .

I saw there on every sidewalk and crosswalk and slimy place in between, a deluge of dough-boys holding plastic bags filled with plastic toys . . . others were journalists in baggy flannel shirts and Chuck Taylor knockoffs. Their faces were hardcoded with a sort of off-the-shelf banality that made me feel as though they were made of flesh-colored paste. Thousands of them, I reckoned, had been squeezed out of tube and fitted into a human mold only hours before, then set free to flap their gums and bite their tongues under the skeleton-frying sun. Some of them were even walking incorrectly.

The whole thing taken together was ghastly and violently idiotic, was bone-chilling in its perfect hideousness. In all my life I had never seen so many bad things corralled together in one place. As this was the twentieth Electronic Entertainment Expo, what I was witnessing had occurred nineteen times before in about as many years, though I was sure this was the apex of its awfulness.

Jack and I were silent as we trudged further into the thing, still unsure why we were at the Los Angeles Convention Center instead of home in Oakland. We had no games to present, no developers to interview. We didn’t have even passes to get inside. We were imposters and intruders, floundering there in the deep. Our presence was even more absurd and meaningless than usual; the thought of even pretending to wave the flag of journalism made my stomach churn like an ocean of oatmeal.

Surely they could all smell it on us. In that vacuum of hatred where the creeps roamed free, we were the most worthless mammals of all. One wrong move, I thought, and they’d take us down and tear our flesh into ribbons, leaving nothing behind for the vultures to pick at. It was a feeling that was not unfamiliar to us.

“I wanted to go to E3 so badly when I was a kid,” I said. “I wanted to be here more than any other place on Earth. Can you imagine that?”

“Looks like a God damn circus nowadays,” said Jack.

“Witness this madness! I mean, look at it!” I grabbed Jack by the shoulders and rotated his body three hundred and sixty degrees. My eyes were wild. “My God, open your eyes, man! Point your peepers at this flaming dog turd in space! Feel something, why don’t you!”

In the midday haze we darted across what seemed like hundreds of lanes of traffic, dodging massive tour buses piloted by bloodthirsty psychos until we reached the main hall, which was festooned, like a bad Halloween costume, with a Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare advertisement.

What a stale thing to behold: another featureless white guy with a buzzcut crouching and holding a machine gun, waiting to run and shoot at strangers until they were fucking dead . . . only for those strangers to be born again moments later, fully formed in fatigues and armed to the teeth, awaiting death a thousand times more until it stopped being fun—if it was even fun to begin with. . . .

Below it was a crass and empty marketing line that I’m sure sounded pretty cool to the idiots whose job it is to ruin the world:

“POWER CHANGES EVERYTHING. 11.4.14”

It sure does, I thought. I stood there on that terrible fake grass sweating like hell and imagined how power had changed everything—how it had created, over many dozens of centuries, the sad pocket of existence I was gazing upon that very moment.

November 4th, 2014 will roll around sooner or later, I thought, and on that day a cultural orgy will surely unfold all across the United States of America. The game will of course sell millions of copies. The straights and squares will go nuts. In the Midwest it will be celebrated in dark and quiet places, and with clammy palms and dead gazes. And then we will inch, all of us, a little closer to the finish line which is called “Death”—where we will be eaten by flames while Lucifer strokes it real hard.

But there were still six months to go before an interactive picture-show would bring upon the end of Western civilization, and so onward I went—to crawl inside that black and ugly heart that dwelt at the center the nightmare world I had willingly cast myself into, if only to say I had seen the God damn thing with my own two eyes before the men with gas masks and machine guns took my own little black heart from me.

We flopped down the sidewalk like a couple of waterlogged dildos toward the shapeless cluster of connecting halls and structures of the Los Angeles Convention Center, all of them plastered with garish ads for Assassin’s Creed: Unity and The Witcher III: Wild Hunt and some godforsaken thing called Evolve, which I knew without knowing anything else about the thing would enable its players to do just the opposite.

Jesus, I thought, who gives a shit about any of this. My mind was reeling, seeing all those reporters and all those news vans, and the all those schlubby twerps with their pocket recorders. And then there were the blameless bastards who looked so lost and confused . . . the ones who had travelled all the way from the Midwest or the East Coast just to feel like they were a part of something, no matter how grotesque and godless that thing was.

I was making a mental inventory of everything that needed to vanish from planet Earth in order for humans to carve out a few more centuries of precious Existence when our half-hearted forward momentum lead us to another strange and frightening place. Behold! the Staples Center . . . from the mouth of which poured hundreds of the same clay-faced wastrels we had seen schlumping around the main entrance.

“Get a load of all these pasters,” I said, referring to the gelatinous clump of paste-colored faces and arms and legs headed straight for us.

Behind the Staples Center was the worst skyscraper I had ever seen. It tore out of the ground like a witch’s finger, hundreds of feet tall, made of mismatched glass, and in the shape of no natural thing. It took up space in the sky, was contemptuous of the world below. I supposed it was a hotel. “And will you look at that God damn superstructure up there!” I screamed. “Can you imagine how many eyeballs were on those blueprints? How many signatures were required to bring that thing into being? Jesus lord in Heaven!”

“It’s certainly not pleasant to look at,” said Jack. He mumbled something else but I didn’t hear it.

I took a joint out of my denim jacket. I lit it right there on the sidewalk—right there under the sun, in front of all those people, in front of the Almighty Himself. And I inhaled deeply till I saw little stars twinkling behind my eyes. My heartbeat increased. My mind cooled.

Now I was badly twisted and several layers above or below reality. The spooky smoke and the stuff from the snuff box was really juicing through me. Switches were flipped. Knobs were turned. The ugliness of the world was amplified tenfold, and so too was my horror of it. Every passing moment was another psychedelic assault on all five senses. If I opened my eyes wide enough I could see the planes merge and separate over and over again; they wavered like a lullaby.

“We’re trapped in an issue of SkyMall,” I said. “What a cruel joke. And not a funny one, either.”

I snapped my fingers. I had an idea. It wasn’t a good one: “Holy lord!” I said to Jack. “Do you still have that tape recorder? We’ve got to show the good people of Earth what this terrible dream sounds like. Not that it’ll make the faintest God damn difference. They don’t care. This is the world they wanted, after all. Still, I reckon we can file all of this under ‘personal research.’ We might even be able to write it off with the IRS.”

Jack took a little black recorder out of his bag. It was ancient and beautiful. He pushed a few buttons in vain. Nothing happened.

“She’s dead,” he said. “For now, anyway. We’d need a couple triple-A’s to get her going again.”

“Then let’s get off Shit Island and find some batteries. There’s got to be an honest merchant left in this city.”

Jack pointed to a deserted street on the other side of the Staples Center. Skyscrapers loomed overheard. I figured it was the downtown area. We adjusted our sunglasses and lurched through that artificial wasteland in search of toxic electrochemical cells. I closed my eyes. I saw ghosts, saw the Founding Fathers weeping softly from the greyness of non-existence. I saw too the infinite rows of headstones at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

I looked back. The Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare ad was billowing in the empty LA breeze.

My God, I thought, just look at what we’ve done.

• • •

Our trajectory toward total annihilation lead us to a subterranean mall a few blocks from the Convention Center. We stepped onto an escalator and rode the damn thing a hundred or so feet below the city. At the bottom it was cool and damp. It was a world forever hidden from the sun.

Behind us was a woman filming a video with her phone. She wanted to make a record of her voyage to that great beacon of commerce beneath the surface.

Unfortunately for her I was there, raving at all the phony plastic people in their phony plastic kingdom. The tiny microphone on the bottom of her phone had no choice but to record the idiotic diatribes of the sulky, ill-tempered white man in front of her:

“Oh, hideous demons! Beautifully compacted garbage! Ravenous faces frozen in horror! Purses and T-shirts and belt buckles bearing the copyrighted emblems of faceless millionaires!”

The two of us nowhere-nothing nobodies approached the black gates of the third-largest discount retailer in the United States. Unfeeling sensors attached to automatic doors read our movements as we neared. They did not see our hearts; that was not their job. Instead they obeyed their simple programming. The doors slid open and we were swallowed into it.

Inside was a funeral home the size of a football field. I saw hundreds of decisions that had been made under fluorescent lights in the top-floor board rooms of mile-high skyscrapers. I concluded that the psychos who had designed the rat’s maze we were in felt nothing but hatred for their customers, for the very people who would continue to make them rich.

Over the PA system I heard the faint tinkling of something that I’m sure someone could argue was music. It was a cover of Randy Newman’s “You’ve Got a Friend in Me,” sung by a chorus of elementary school children. This answered a question in my brain that I did not know existed, which was, “Is it possible to somehow make ‘You’ve Got a Friend in Me’ exponentially worse?”

Jack and I ceased to be journalists. Now were wounded animals encircled by a gang hyenas disguised as mothers pushing strollers. They wore leopard-print yoga pants with neon jogging shoes. Their skin was clear and smooth. They were made of pizza dough from an alien planet.

“Jesus!” I screamed. “What a mindjob! They’ve got us now—they’re never going to let us go!”

“This way,” said Jack. He grabbed my arm and we raced past the crowds and through the grocery section to a wall of flat-screen televisions at the back of the store. The televisions, dozens of them, were displaying the same catastrophically bad fifteen-second video. The video was on loop. It was an ad for an album created by four people who appeared to belong to the Aryan race.

I opened my mouth to scream, but before I could utter a single strained note, Jack again grabbed my arm, and again we swooshed through the place at a thousand miles an hour. Soon we were alone in the toy aisle. Some of the walls were pink. Others were blue. Curiously, some were yellow.

“Yellow walls!” I said. I figured it out immediately. “I reckon this is where they put the toys that can’t be easily categorized—toys that are intended for boys and girls. What the hell kind of message is that? All of the walls should be yellow. . . .”

We had escaped the main throughway and were hiding in an aisle populated by doe-eyed baby dolls. I took one off the shelf and examined its packaging. On it was brainless nonsense—the hieroglyphics of a dying species.

“Bitsy Burpsy Baby,” it said. And below that: “Burping time is full of cuddles.”

I read on: “Burp cloth changes color when wet. Feed her the bottle. Change her diaper when she wets.”

“Get a load of these,” said Jack. He pointed to a row of dolls sealed inside little canvas backpacks. The backpacks were shaped like coffins. There was a thin layer of transparent plastic where the doll’s face peered out from.

I had imagined we would find peace in the banality of the place. Instead we had uncovered the same timeless horror as before, only it was wearing a different Halloween costume. The thing was truly inescapable. Civilization had failed. We are doomed, I thought, all of us. Not one spared.

God knows how long we stood there examining those hunks of smooth plastic molded to look like human children, which cost $40 a pop and burped and farted and threw up at the press of a button—but at some point a seam inside me burst, and my disastrous personality poured out from a small hole, filling the warehouse-sized room with a sort of spooky muck that could only be perceived by the hyper-sensitive and the super-depressed.

Jack perceived it. He knew I was in a bad way, that my mind was at its most fragile state. Before I could dismantle myself or implode or whatever else, he ushered me to the battery aisle. There I grabbed a pack of triple-A’s and we raced to the door, away from the burping babies and the minstrels of the Master Race—away from “You’ve Got a Friend in Me.” To hell with giving these creeps any money, I thought. I stuffed the pack inside my jacket and breezed through the security sensors. The automatic doors scanned my shape and parted in the middle. I stepped through them and became a criminal.

Outside the air was cool and thin. I hallucinated birds chirping. The sun was still aching to get to us.

“Smelled like God damn death in there,” I said. “I don’t know how much more of this I can take. My constitution’s all out of whack. My mind is long gone, never to return. . . .”

“Let’s find a quiet place,” said Jack. “It would do us some good.”

On the way back to the Convention Center we found an open gate between two brick buildings. The gate was shiny and ornamental, which meant only rich people who lacked self-awareness were intended to pass through it. We laughed like hell and passed through it as well. At the far end of a long corridor was a sort of courtyard. There we found marble benches and a small trickling fountain. Sunlight climbed over the low wall in the back.

We weren’t alone in the courtyard. We saw nicely-dressed middle-aged white people here and there, and young men in fancy serving uniforms as well. The men in uniforms were not white. I guessed they were catering some event. Everyone was talking quietly or smoking alone.

Jack and I sat down on one of the marble benches surrounding the fountain. He lit a gold American Spirit. “These damn things are shredding my throat,” he said. “Gotta switch to the blues if I want to make it to old age. And maybe I don’t. . . .”

“I sure as hell don’t,” I said. “Not if it’s going to be like this.” I still had half a joint left in my coat pocket. I lit it and took a few long drags just to scramble some shit around a little.

I ripped the batteries out of their plastic cradle and handed them to Jack. He loaded them into the recorder and turned it on, hoping to pick up some ambient noise. I gave an impromptu speech on how the new American century was built upon thousands of layers of dog feces. Someone coughed. A bird cried out in the sky. I heard teeth gnashing and pigs squealing and demons weeping deep below. I wondered if the recorder heard it too.

“We can never let the CIA get ahold of this tape,” said Jack.

• • •

PART THREE:

BEARING WITNESS

I half expected the Los Angeles Convention Center to have burned to the ground in the hour or so that we were away from it. “Prepare yourself,” I told Jack en route. “Those freaks will be rioting on the crater rims of great smoldering fires when we return. There will be madness for miles—beheadings, torture, fornication in the streets—you name it. Hell, I wouldn’t be surprised if they’ve already wheeled out the guillotine. Damn thing’s probably lopping heads off in front of the Staples Center as we speak.”

I closed my eyes and had a vision of the fifteen-foot-tall plastic robot sculpture from earlier. Hung around its neck were the lifeless bodies of games journalists and PR drones who hadn’t been fast enough to outrun the mob.

“Strangled with Call of Duty T-shirts!” I screamed. It was part of a larger conversation going on inside my head. “Swollen legs wrapped in argyle socks and bootcut jeans, just a-swayin’ in the breeze!”

“Get it together,” said Jack. He had the recorder in his hand. “We’re getting close now. You brought us here, you fool. Now let’s do what we came to do.”

“Yes!” I said. “You son of a bitch, you’re right. There is work to be done. We’re on the clock, God damn it. Paste Magazine isn’t going to pay us for the tape alone. No, they’ll want words too.”

It was time to slink in and get the story, whatever it was, and then get the hell out. Climb aboard the money-go-round and cling to the railing as long as we could. But we had to keep a low profile. There was no telling what those pimps and marauders would do to us if they discovered we were journalists. Sure, we were all destined to be bulldozed into mass graves, but not yet. The story had to get written first—even if the story was worth less than a sheet of toilet paper. They must know of the conspirators of their doom, I thought, of the architecture of their sad and whimpering end. They must!

Jack flicked on the recorder as we neared. We were ready to do battle with great evil. He would capture the funeral toll of a dying world, and I would write down every paranoid delusion I had in a notebook.

But soon it became clear that absolutely nothing had changed. The sidewalks weren’t slicked with blood, and no one was screaming. E3 was still the somber constellation of micro-tragedies it had been before. If anything it appeared more lifeless. I heard a few scattered laughs and that was it.

“Damn!” I said. “We must have missed it. They’ve already carted off the bodies.”

“Maybe we should try to get inside,” said Jack.

“Ah—yeah. We should. They’ll stop us, though, I’m sure. We don’t have badges. In fact we have no credentials at all.”

“Paste didn’t send you anything?”

“Hell no. Are you joking? They don’t even know who I am.”

“What do you mean?”

I shrugged. “This was Cara’s doing. I think she was trying to throw me a bone, God bless her. She wants to augment her own piece with whatever I send her. If we can’t get inside, then I have nothing to send her.”

“Well, shit. Let’s try to sweet talk our way in. And if they don’t go for it, we can always storm the place and hide somewhere till the heat cools.”

The main entrance looked like the most promising way of getting in. There were four security guards in baggy suits standing near the automatic doors. All of them looked bored as hell. People were coming and going so quickly that even a half-assed sneak-in seemed feasible. I figured maybe we could bribe a small group of badge-toting twerps to let us slip by with them—perhaps if we stayed on the outside of the group, or hovered in the warm center.

As we glided through the concrete hell surrounding the Convention Center, we passed independent game developer Nina Freeman. She was sitting on alone on a bench. I had spotted her pink hair from a half mile away. I snapped my fingers. I pointed at her. “Nina Freeman!” I said.

“Hi!” said Nina Freeman. She waved to the pale and grease-slicked stranger who knew her name.

We kept walking. “You know her?” said Jack.

“Not really, but I sure wish I did. I met her at a party in San Francisco during the Game Developers Conference in March. Tim and I demoed ‘VIDEOBALL’ in the living room of this house she was staying at. She probably has no memory of this. There was free beer, so I was drunk as hell. I can’t imagine I said or did anything memorable once I got sauced. In fact I think I offended a lot of people there.”

“Offended them how?”

“I don’t know, just by talking.”

I saw a tall man in a pink T-shirt and black blazer standing outside one of the side exits. He was alone. It was John Legere, the President and CEO of T-Mobile. I snapped my fingers and pointed at him. “John Legere!” I said.

“Hey man,” he said. He looked up from his phone. “How you doing?”

“Ah, baby, I’m all right. Sad to be here, but here nonetheless.”

“I know how that goes.”

I walked up to him and extended my hand. He locked his hand with mine and gave it a firm pump. “You’re a cool dude,” I said. I meant it. John Legere really is a cool dude.

“Thanks!” said John Legere.

Now we were moving again toward the shoreline of that bleak cosmic ocean called the Electronic Entertainment Expo; now we would force our way in. I scanned the entrance. Jack stood with his back to mine, watching the rear. “There’s a tank behind you, and in front of me,” he said. I cocked my head back. Sure enough, there was an honest-to-God blow-the-shit-out-of-everything tank parked on the sidewalk. Women in camouflage bikinis had their arms and legs draped over the turret. They were posing for photographs. Their paychecks, I knew, were signed by the same foul reptiles who had dreamed up everything around us.

I peered inside the Convention Center. Nothing but a few security guards and a smattering of bread-faced burrito-filled humans wearing messenger bags. But further inside, I knew, was the whiz-bang dick show that people traveled far and wide to see—that great orgy of light and sound raging in the depths of the main hall. I had to see the cruel circus for myself—from behind big white sunglasses and several layers of uppers and downers—and, like John of Patmos, record what I had seen and heard.

What awaited us in the main hall? I wondered. The black throne of Satan? Ritualistic suicide, maybe, and animal sacrifices. Those bastards were probably in there wearing goat skulls and black robes. All the moaning and chanting! This was going to be a sight to behold, no doubt.

“Who do we know at the New York Times?” I said. “If we’re going to risk our lives for this, I want front page coverage.”

“Huh?” said Jack.

“Never mind. Let’s get in there.”

“Security looks tighter than I thought.” Jack squinted his eyes. “We’re going to have to be stealthy. Look for patterns, routines—anything. The guards are bound to slip up at some point.”

“Forget that. Even if we did get inside, we’d still be badgeless. There are dozens more of those ghouls inside. If they catch us without the mark of the beast, they’ll put us in front of a firing squad.”

“We could beat up some kids and take theirs.”

“Yeah. It may come to that. But I’ve got an idea. God damn it, man, turn that recorder on and follow my lead.”

We approached the most dimwitted guard of the four. “Sir,” I said. “I realize you’re busy keeping this place safe, but could we trouble you for a moment?”

He narrowed his eyes. “What’s up?”

“Baby, listen. The two of us, see, we’re reporters for the Toronto Star. And we’re in one hell of a pickle. We’ve got to get into this building—” I pointed to the molten hellscape behind him. “But we don’t have our badges. A couple of rotten bastards mugged us in North Hollywood this morning. Real crooked fuckers. Took our passports and everything. Can you believe it?”

The guard tensed. He shook his head. “Can’t do it. I have no say in—”

“The LA office is out for the day. They’re inside the Convention Center already, getting the story that should by all rights be ours. What am I going to tell them? That I came all the way to Los Angeles to cover the convention from the parking lot? I can’t go back to Toronto with nothing.”

He kept shaking his head. “There’s nothing I can do. I have no connection to the convention itself. We’re just hired to secure the building. They told us, ‘Badges get to go in.’ So if you don’t have a badge, you can’t go in.” He must have seen the agitation on my face, because he smiled awkwardly and added this: “But hey, Red Bull is hosting a free party across the street. You don’t gotta have a badge for that.”

I knew which party he was talking about; we had walked by it earlier. Everyone within a five-mile radius had their senses held hostage by its mere existence . . . all that horrible music, all that strange laughter. It was a freak show on wheels—a broth of human wreckage. I wanted no part in it. I clenched my teeth. “You expect me to flail around with those degenerates?”

“Man, look, I can’t let you guys in if you don’t have badges. Those are my instructions.”

“‘Those are my instructions’? Is that really what you just said? Man, are you going to quote the entire Gestapo handbook, or is this all we get?”

To this the guard said nothing. He looked away from me. I knew there was no getting through to the son of a bitch. I signaled to Jack. We pulled back from the entrance and retreated to a shady column on the far end of the promenade.

“This is useless,” I said. “Those jerks. Those pigs! They want us marked, damn it, and there’s no way we can fake something like that on short notice. And to hell with trying to get press passes. The deadline was probably weeks ago.”

“We could call in a bomb threat.”

“In a post-9/11 world? Good luck with that. I’m putting out an APB. Someone we know has to have a badge they’re not using.”

I sent messages to my friends in the quote unquote industry—to Tracey Lien, the journalist, and to Brandon Sheffield, the independent game developer.

Tracey wrote back immediately saying the badges were more or less photo IDs. Neither of us looked anything like Tracey, so that was out of the question. We aimlessly shambled around the sidewalk until Brandon replied, but it was more bad news. He said he actually needed his badge because he was doing a series of interviews. He graciously invited me to a “barcade” later that evening, but I declined. I told him I didn’t trust portmanteaus. He apologized and wished me luck, but I knew we were fresh out of the damn stuff.

“They’ve got this place sealed up tight,” I said to Jack. “We’re wasting our time out here.”

“So it’s over then?”

“I reckon so.”

We stood there for a few minutes, my partner and me, gazing at the great big nothing in the sky, not saying a word. My face was grim as hell. I had my hands on my hips. Jack was sucking down another cigarette and rewinding the tape recorder. It made a mad, jittering noise.

“Welp!” I said finally, and began walking away from the sun-blasted nightmare ruins of the Los Angeles Convention Center. The drugs were wearing off and the story was dead. The reptiles had won. All that was left to do was go home and get old.

• • •

PART FOUR:

HOPELESS ON HOPE STREET

Jack and I shuffled back to Hope Street where the Doomsmobile was parked. There was another hour left on the meter. We sat in the back seats and puffed on cigarettes and read from a Chinese newspaper I’d taken from a coffee shop in Oakland a few weeks before. The hateful sun beat down on the roof.

“How much was Cara going to pay you?”

“A hundred bucks. And man, let me tell you, I really could have used that hundred bucks. I have no idea how I’m going to pay my rent next month. I . . . Jesus, I took off work a whole week. I think I may have even dumped a girl to come here and write this damn thing. I told her it was important, when it most certainly is not, and never was, and never will be, now that there’s nothing to show for it anyway. . . .”

“Hm.”

“Hell, this whole ordeal is going to end up costing me money. Should we even bother looking at the ledger? It’s going to be awful, seeing how much cash we’ve blown for no good reason.”

Back in Oakland, Jack had agreed to be in charge of numbers and data—and anything involving having to have a normal conversation with strangers, particularly squares. I had failed miserably at my tasks—securing press credentials and lodging—but I knew Jack was keen on getting the job done.

He took a little notebook out of his breast pocket. He flipped through a few pages until he found a list of our expenses. He scanned it up and down, twisting his lips. “I haven’t tallied it up yet, but it definitely ain’t pretty,” he said.

“Just lay it on me, man. I’m ready.”

“Well—it looks like we’ve already spent over three hundred dollars.”

“Holy lord.”

“Yeah.”

“We’ve been here for less than twenty-four hours. Where in God’s name did the money go?”

“That’s what everyone wants to know. . . .”

“Do we drive back to Oakland? This expo thing goes on for another three or four days. We’d be hemorrhaging money the whole time.”

“We could leave now, I suppose.”

“Yeah . . . but we’d be stuck in traffic till midnight, maybe. Hell, it would take us two hours just to get out of Los Angeles at this point. These fuckers have got us pinned against the wall.”

“We could always stay another night. See how it goes. Park somewhere nearby and stay put till morning. Don’t forget, we’ve still got those mushrooms in the snuff box.”

The mushrooms! I had forgotten all about the mushrooms. A friend had given them to me the previous month, saying he’d eaten way too many on his thirtieth birthday, and as a result of all the strange and terrible things he’d experienced that night, he had to offload them as quickly as possible—before he ruined his mind for good.

“Strange and terrible” was an irresistible combination to me. We had enough caps and stems in the box to have a real wild time. But where?

“Do you remember the observatory from Rebel Without a Cause?” I said. “The one on top of that hill?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s Griffith Park, which is a few miles north. We could go there right the heck now and get twisted.” I slapped his thigh as hard as I could. “Jack! Baby! Can you imagine looking through that telescope once we’re all doped up and stupid? Picture the moon! For Christ’s sake, picture Mars!”

His answer came swiftly: “Lead on, you gorgeous son of a bitch. Lead on. . . .”

• • •

PART FIVE:

THE WOMAN OF SILVER LAKE

The 101 was backed up for miles, one great big parking lot in Hell, so we sped onto I-5 headed north towards Griffith Park. Jack revved the Doomsmobile hard and heavy while I navigated and did an inventory of our rations. A cursory inspection revealed that most of the fruit and vegetables had wilted in the heat. The brown grocery bag, once brimming with delicious vitamins and proteins, was now little more than dead weight. In a P71 Police Interceptor, gas mileage is everything, and we really needed to make those miles count. And so, to lighten our load, I began tossing dozens of pale, rubbery carrots and celery stalks out the window at about ninety miles per hour, watching them flop to the ground and bounce up to hit the windshields of the poor souls behind us. A real freakish scene unfolded in the sideview mirror as cars weaved left and right to avoid making contact with our rotten produce.

“We need supplies before we poison ourselves—before we turn the inside of our brains into a beautiful psychedelic amusement park.” I rattled off the necessities: “Fruit . . . coconut milk . . . sunblock. God damn it, we’ve got to have it all. Especially the coconut milk. I don’t even want to think about not having coconut milk with us tonight. It is the key which unlocks the superhighway of the mind and—Lord, I can’t believe I’m about to use this word—maybe also to the soul as well. . . .”

Jack spotted a Trader Joe’s in Silver Lake, just off the highway. Despite our speed, he took the exit nice and smooth, and parked the Doomsmobile in a prime spot near the front of the store. We flung the doors open and hopped out onto the sidewalk. We had to be quick; the sun would be setting soon, and I wanted to be on the big ramp-up to total insanity before all that fire plunged into the ocean, leaving us sinners to rot in the dark. . . .

Once inside the store we split up to hurry the process along. I volunteered to collect the fruit and sunblock. Jack was on coconut milk detail. I walked to the back and got a little baby cup of coffee from the sampling kiosk, downed it quick like a shot of whiskey, and immediately went to work loading my arms with bananas and clementines and Gala apples. On my way to the register I scooped up a tube of sunblock.

The place was crammed with mutants of every kind, and so there was a cashier stationed at every register. As a worthless son of a bitch who often has nothing better to do, I am a veteran when it comes to turning little errands like this into something else entirely. Gazing at the long row of cashiers in their colorful Hawaiian T-shirts, I tried to pick out the most interesting one to talk to. It would be a short conversation, and one of hardly of any consequence, but you never really know where these things might take you until you embrace the weird mystery of it. At least for me, to play the game is to win the game . . . only then because I had already lost everything else.

At one of the express lanes, I caught sight of the back of a young woman’s head. Her hair was the color of Mars. She had a tattoo of a sinister multicolored butterfly on her death-pale bicep. She had the complexion of a ghost. She was wearing high-waisted jeans. I couldn’t see her face or look into her eyes to determine if she was a Feeler or a Feel-Nothing, but I myself had a good feeling. I walked across the length of the store and got in her line. I dumped a pile of fruit onto the register and stood back.

When I did look up at her, I got nervous as hell. I don’t usually get nervous around anyone. Lord! Those cat eyes! That beautiful face! Those high-waisted jeans! Those witch rings! I thought to myself, “Sweet baby Jesus, infant savior of this cruel Earth!”

What I said aloud was this: “Uhhhhhh. Lord. Hello.”

“Hi!” she said. “You have a lot of fruit. . . .”

“Oh, God, yeah. I came all the way here from Oakland on a rotten assignment. It . . . ended up being a total bust. So now I just need a safe place to hang out and eat these here bananas. I guess I’m going to the Griffith Park Observatory to do that.”

“It’s really cool up there! There are paths leading into the hills. You could eat the fruit up there.”

“Yeah. I’m definitely going to do that. I’m going to pay my respects to James Dean, too.”

“There’s a memorial for him by the observatory. Like a bronze bust of his head.”

“That’s where I’ll go first. Probably give that dude half of my banana. Maybe have a smoke in his honor. Other than that I just want to see some stuff, you know?”

She handed me a receipt. “Well, good luck to you.”

I read her name tag. It said “Danielle.”

“Good-bye, Danielle,” I said. “I’m going now, I guess. And I’m sorry I just used your name. I know that’s annoying when people do that.”

“It’s OK.” She smiled. It was a hell of a smile. God, that smile! I was beginning to get sentimental, seeing that smile, so I forced myself to walk away. I turned around and gave her a sort of half-hearted Elvis lip curl. I was holding a bunch of fruit. My skin was inflamed from too much sun. I felt like a fool. I kept moving. I stepped through the automatic doors and pointed myself toward the Doomsmobile.